In storytelling structure, people use the term “act” rather broadly and vaguely. Most in the writing community break stories down into three acts: beginning, middle, and end. But if you asked many writers what an act actually is, they would probably give you blank stares.

Despite acts being key structural units in stories, they don’t get a lot of attention.

And when they do, they are often treated simply as containers to fill with beats from a beat sheet.

Luckily, the basics of acts aren’t too hard to grasp, if you already know the basics of structure.

And once you grasp acts, your whole story will have not only better structure, but better pacing and better direction.

So let’s unpack the act.

—

As mentioned, those who usually give the act any mind, are often following a “beat sheet.” This is a list of key moments (or “beats”) that are supposed to happen in a specific order, and usually, at a specific time, to make a story more satisfying (put simply). Beat sheets can be very helpful and very effective. Two of the most popular are Save the Cat! by Blake Snyder and Vogler’s version of The Hero’s Journey. Another common structural approach is 7 Point Story Structure.

Often beat sheets will be separated into acts, so if you are familiar with them, you may have some understanding of what’s supposed to happen in each act.

If you aren’t familiar with them, that’s fine too.

Basic Story Structure

I’m going to explain acts from the bottom up–and we’ll get back to the beat sheets for those who like to “beat” out their stories.

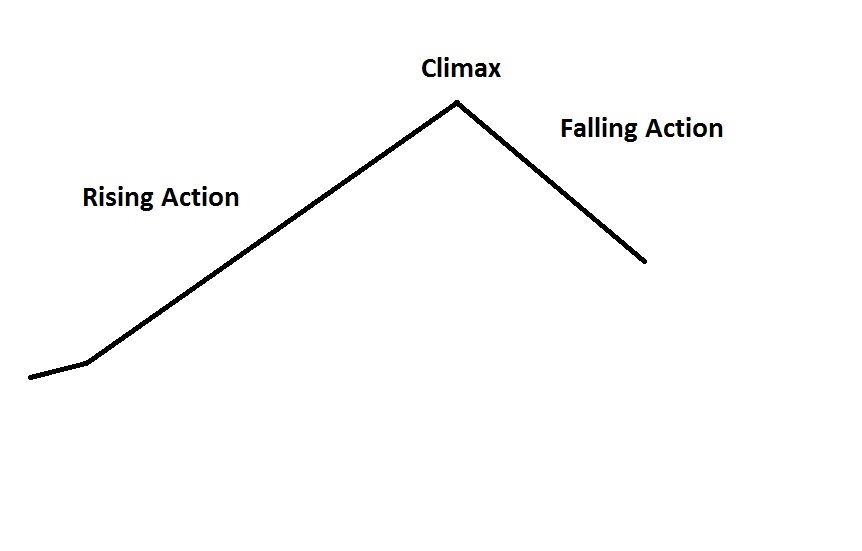

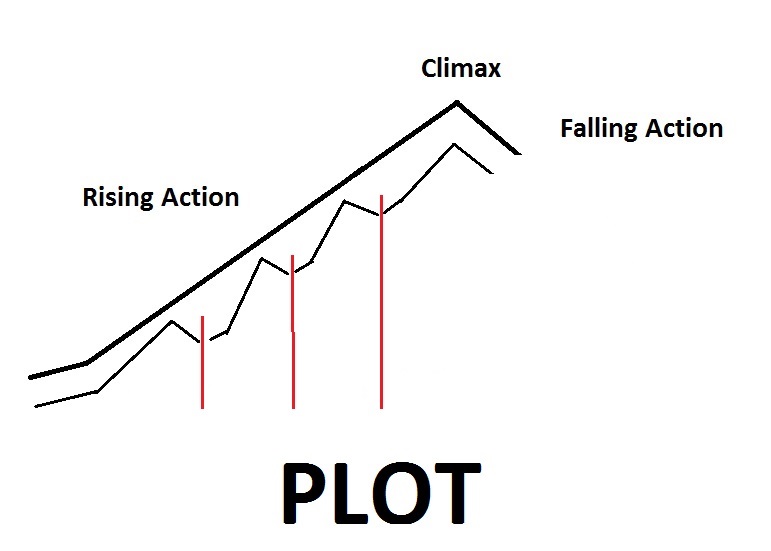

At the most basic level, the structure of a story (almost) always looks like this:

It has a rising action, climax, and falling action.

If we zoomed in a little more, there would be an inciting incident. This is the turn in the beginning of the story that kicks off the main plotline–it often appears as an opportunity or a problem for the protagonist.

- Charlie Bucket finding a golden ticket.

- Peter Parker getting bit by a radioactive spider.

- Boo coming into Monstropolis in Monsters Inc.

These are all examples of inciting incidents.

From there, the story escalates, more or less, until it gets to the climax, where the main conflict between the protagonist and antagonist hits a peak and gets resolved. This creates a turn that then leads to the falling action.

That’s basic structure.

Basic Structure and Structural Units

But it’s not only basic structure for a story as a whole, it’s also basic structure for just about any solid structural unit. Ideally, scenes should have this structure, sequences should have this structure, and yes, acts should have this structure.

Each unit fits inside the bigger unit, like a Russian nesting doll, or a fractal.

The difference is that, the smaller the structural unit, the smaller the impact.

So the climax of a single scene will be smaller than the climax of a sequence. (This term isn’t used very often, but a sequence is a string of related scenes, that don’t fill up a whole act.)

The climax of a sequence will be smaller than the climax of an act.

And the climax of an act will be smaller than the climax of the overarching story.

Basic Act Structure

Nonetheless, other than the story as a whole, the act is the biggest structural unit. This means each act should crest into a big turn in the story.

It’s not just that the story has one major peak–a turning point–at the end.

It should have several big peaks along the way.

It should also have several “valleys” along the way.

While the overarching story is escalating in general overall, it still has rises and falls in each act.

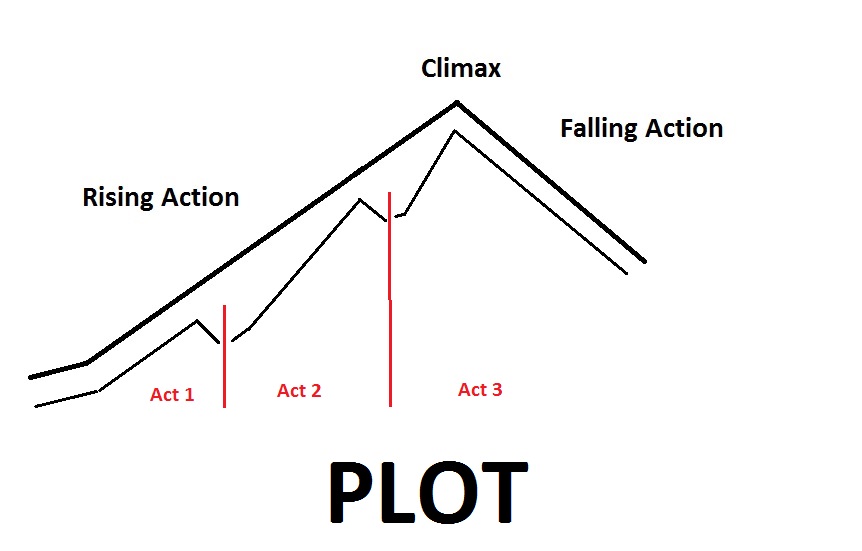

Most commonly, people view stories as having three acts.

This means the structure will look somewhat like this:

It’s also equally common to split the middle act in half. Frequently, in the middle of the second act, there is a major turn, called the midpoint (you may have heard of it). If this moment is major, it’s often more helpful to picture the structure with the second act split into two, something like this:

One may arguably call this a four-act story, but to keep with the most commonly used terms, it’s probably better to call these pieces, Act II, Part I & Act II, Part II.

When you look at this structure, you may realize something . . . there is no saggy middle! There is also no boring beginning, or lackluster end.

This is because there is a rise, peak, and fall within each act (and arguably two in Act II).

Frequently, people divide these act pieces into quarters. Not every writer likes using percentages, but it’s the best and easiest way to indicate when and where something in a story should typically happen–so we’ll use them.

- Act I: 0 – 25%

- Act II, Part I: 25 – 50%

- Act II, Part II: 50 – 75%

- Act III: 75% – 100%

Please note that the percentages aren’t laws; they are more like guidelines. But we need the guidelines to even have a proper conversation about acts. Once we understand the guidelines, we can play with variations for different effects, but we need to lay a foundation first to get anywhere.

The beautiful thing about this, though, is that you know you need to hit a peak in each of these quarters.

Now, occasionally, writers will cut some or all of the falling action off the structural unit. This is rare for the overarching story (but it does happen!). It is more common for smaller structural units. So don’t panic if all your units don’t have the “fall” into the valley.

Acts and Structural Pacing

The point is, you have peaks and valleys.

And it’s helpful to have them in the proper places. Why? Because this is what controls structural pacing.

Pacing is more than word count. In fact, pacing more closely links to structure. When the structure of any given unit is solid, the pacing will almost always be exactly what you need. The exception to this is when you are looking at the lines themselves–that’s when things like word count become more important.

Generally speaking, solid structure = solid pacing.

This is why when you understand acts, you’ll be less likely to have pacing problems in beginnings, middles, or ends (no saggy middles!).

Pacing gets tighter the closer it gets to the peaks, simply because the plot itself is becoming more intense.

Then it gets more leisurely and loose in the valleys, as we fall and/or begin the next climb.

Each Act’s Climax

Act I

So, when you are writing the beginning, you know you need to be climbing toward a big turn, which will hit before the middle.

What is this Act I climax?

Well, depending on what approach you are using, people will call it different things. (This is where those of you who are familiar with beat sheets pull yours out.)

- In Save the Cat! This is the “Break into Two” beat.

- In Vogler’s Hero’s Journey, this is “Crossing the Threshold.”

- In 7 Point Story Structure, this is “Plot Point 1” (sometimes alternatively called “Plot Turn 1”).

If you aren’t familiar with any of these terms, that’s fine, but know Act I has a climactic turn.

This climactic turn works by locking the protagonist with the main conflict. It is typically marked by the protagonist’s choice to step forward, through a “Door of No Return” (i.e. Crossing the Threshold) or a “Point of No Return” (i.e. plot point). It’s what “breaks” the story into Act II.

The protagonist definitively chooses to go forward on the journey of the primary plotline. This is then usually followed by a transitional segment, that takes us into the “valley.” . . . There is a lot more I could go into here, but it’s beyond the scope of this article, so let’s move on.

The falling action is often a reaction segment–where the character is reacting to what just changed at the peak. Once the character has at least some sense of their situation, they usually start “climbing” toward a current goal (rising action).

Act II, Part I

Near the halfway mark of the story, you typically hit a climactic peak again. A big turn. People most frequently call this the “midpoint.” It usually involves the protagonist gaining new, important information that helps him move forward more aggressively, or rather, actively, against the antagonist. But it may be marked by a big victory or failure for him too.

The point is, there is a turning peak.

. . . which leads to “falling” into a valley . . .

And again, the falling action is often a reaction segment to whatever big change–revelation or action–just happened.

Act II, Part II

Once the character gets some sense of the situation, you know what she’s going to do? Start the climb toward the current goal. Rising action.

And of course, the climb is never easy. Every climb has conflict and stakes–that’s the only way to escalate the story (in other words climb the rising action).

She hits another major turn.

- In Save the Cat! this moment coincides with the “All is Lost” beat.

- In Vogler’s Hero’s Journey, it’s “The Ordeal” beat.

- And in 7 Point Story Structure, this is (arguably) Plot Point 2 (but there is some ambiguity on how that term gets used in the writing community).

If you don’t know those terms, that’s fine, but just know that this is the major climactic moment of Act II (Part II).

And, most frequently, it leads to the biggest “fall” of the story–a big lully drop to a low, low valley. It’s usually the largest reaction segment of the story.

Well, guess what happens next?

Act III

After the character has taken some time to wallow in his failures, he’ll find his footing and start the last climb–to Act III’s climax, which is (almost) always simultaneously the climax of the whole story.

And that’s the basic structure of the story, through acts.

Acts and Inciting Incidents

Now, if we were to zoom in a bit more, we would likely find that each act also has an “inciting incident”–it’s usually what kicks off the next climb. It’s what gets the character to leave the valley and come up with a plan about what to do next (whether or not the plan plays out as intended).

The most recognizable one in storytelling approaches (other than the first one, in Act I) is Act III’s.

After Act II, Part II’s major lull, usually the protagonist gains something that pulls her out of the lull. If you are following along with your beat sheets . . .

- Save the Cat! calls this “Break into Three.”

- Vogler’s Hero’s Journey calls this, “Reward: Seizing the Sword.”

- And (this is where the ambiguity creeps back in), this is often lumped in with “Plot Point 2” in 7 Point Story Structure.

But Act II will also usually have its own “inciting incident,” something that gets the character on track for the next climb.

And . . . if we went much deeper into structure, I’d probably need to fill up a whole book. So, we’ll end there.

Just make sure to mind the peaks and valleys of your acts–your story, agent, editor, and readers will thank you for it. Even if they don’t recognize what you are doing, they feel it.

(And you’ll probably thank yourself for it too!)

About September C. Fawkes:

Sometimes September C. Fawkes scares people with her enthusiasm for writing and storytelling. She has worked in the fiction-writing industry for over ten years and has edited for both award-winning and best-selling authors, as well as beginning writers. She runs a writing tip blog at SeptemberCFawkes.com (subscribe to get a free copy of her booklet Core Principles of Crafting Protagonists). When not editing and instructing, she’s penning her own stories. Some may say she needs to get a social life. It’d be easier if her fictional one wasn’t so interesting.

***

Coming Soon on Apex!

Wednesday 7 pm – Accelerator Call – Forrest Wolverton

Wednesday at 7 pm Mountain Time (9 pm EST)

Description:

Each week in Accelerator calls, Forrest Wolverton uses NLP and other tools for the mind to motivate and help you get past the obstacles in the way of your writing. He will help you become the best writer you can be. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. Listening to Forrest is a little bit like listening to Dave.

Apex is one of the few writing groups with our own world-class and expert motivational speaker!

To join any of Apex’s calls, simply sign up at apex-writers.com; once you become a member, click on “Upcoming Events” for the call links.