How to write a novel–whether you are a beginner or a professional (or something in between).

Many people dream of writing a novel (or of writing their next novel), but making that dream a reality requires effort and patience. It also helps if you know what you are doing.

Luckily, we’ve put together this step-by-step guide for you.

How to Write a Novel, Step by Step

1. Find an Idea

The first thing you need to write a novel, is an idea. This can come from anywhere—a conversation, a dream, a recent vacation, a breakup, or a post you saw online. You can even draw inspiration from your favorite stories, whether they be novels, movies, shows, or games.

The idea needs to be something that sparks your interest (or even better, your passion). And it needs to be something you could (eventually) write a novel-length story about. So pick something you likely won’t get bored with.

One popular way to generate ideas, is to start asking “what if” questions. What if a baby somehow destroyed the greatest dark wizard of all time? What if children had to fight to the death in a televised reality show? Or what if someone lived in a brainwashed society, and only he knew the truth?

It’s often effective to pair contrasting concepts: a baby destroying a dark wizard, children fighting like gladiators, a wise person surrounded by the foolish. This creates irony and implies tension. The concepts sound like something to dig deeper into.

You may want to brainstorm more ideas related to the one you’ve chosen. (You may also want to consider if your idea is worth writing about.)

The four major components of stories are character, plot, setting, and theme. See if you can come up with some ideas for at least the first three.

Also, consider what genre you want to write in, and generate ideas that fit that genre. While it’s possible to mix genres, usually stories are more successful when they fit inside one.

2. Figure Out if You are a Planner or Pantser

Generally speaking, at the basic level, there are two types of writers: the writer who plans beforehand by creating an outline as a roadmap, and the writer who prefers to sit down and discover her story as she goes. J.K. Rowling is a planner and Stephen King is a pantser. Truth be told, though, this is really more of a spectrum. You don’t have to be 100% one type or the other, but most writers will lean toward one type.

If you are a planner, you like to know the ending of the story ahead of time, as well as the pitstops it makes along the way. You may write out a summary beforehand, use notecards or software to map out events, or jot down key elements of individual scenes.

If you are a pantser (a term that comes from the phrase “by the seat of one’s pants”), you likely feel as if the story is telling itself to you as you write. Or, it seems as if you put the characters in a situation, and simply report what they do next. Pantsers are also called “discovery writers,” because they discover the story as they go.

Many writers are somewhat of a hybrid. Pantsers usually benefit from at least a little planning, and planners usually benefit from at least a little discovery.

Regardless of whether you plan or pants, a solid story will need the following things.

3. Develop a Main Character

The main character, also known as the protagonist, is the most important character in the story. It’s who the story happens to, or perhaps more accurately said, who is making the story happen. The word “protagonist” means “first combatant,” so this is a character who is trying to combat something (whether internally or externally). This character should be the most active (or one of the most active) when it comes to solving the problems of the main storyline.

A common misconception is that the protagonist must be a hero. While that is what’s typical, he can also be a bad guy or a morally gray character.

While many newer writers want to focus on the appearance and surface-level details of their protagonists, it’s usually best to address these core elements early on:

- An abstract want

- A concrete goal

- A ghost (backstory)

- A character arc

Let’s briefly go through each.

The Abstract Want

There is something that your protagonist wants desperately that she keeps close to her heart. It’s what motivates her to do what she does, and often, to say what she says. It’s also something she wants bad enough to consider acting in ways she wouldn’t ordinarily, if it means getting that want.

While the character may want concrete things as well, keep this particular element abstract. Does she want power? Love? Safety? Recognition? Peace?

Luke Skywalker wants to be great. Katniss Everdeen wants to survive. Harry Potter wants love, belonging, and family. And Alexander Hamilton wants to build a legacy. These wants drive their major choices.

It’s okay if you come up with more than one want, but try not to have more than three. Remember, this is a driving force, and a top priority for the character—we can’t have ten “top priorities.”

A Concrete Goal

Since the character deeply wants his abstract want, he’ll naturally try to satisfy that want in concrete ways. This creates the goal. Luke plans to go to Academy. Katniss intends to win the Hunger Games. Harry wants to stop Voldemort to save the Wizarding World (where he has found love, belonging, and family). And Hamilton strives to be a war hero.

Your protagonist needs to have a concrete goal for the plot to be satisfying, so don’t skip this. How can his abstract want manifest into a concrete goal?

Again, it’s okay if he has more than one goal, and it’s even okay if the goal changes or gets added to (like Luke’s and Hamilton’s), but he should have at least one goal he can act toward. It needs to be a goal that is measurable, meaning the audience can visualize what success looks like. They will know when the character “makes it.”

A Ghost (Backstory)

Something in your protagonist’s history led to her having her abstract want to begin with, or at least, a key moment illustrated how bad she wanted her want. This abstract want usually comes about because of a significant, often traumatic event (or events) that shifted the protagonist’s worldview.

Katniss is driven to survive, because after her dad died, she was starving, and when Peeta gave her bread, it inspired her to become a survivor. Harry yearns for love, belonging, and family, because he was dropped off at an abusive aunt and uncle’s house where he doesn’t have that.

This past event is called a “ghost” because it often haunts the character. It’s also known as an “emotional wound,” and it’s usually the most important part of your character’s backstory.

You can learn more about ghosts here.

The ghost also usually preps the protagonist for his character arc. . . .

A Character Arc

A character arc is how a character grows through a story. At the most basic level, there are just two ways your character can grow:

- The character changes (has a transformation).

- The character increases his resolve by remaining steadfast (becomes more of something).

And there are two types of each.

- Positive means the character became someone better.

- Negative means the character became someone worse.

This means you have four options: positive change, positive steadfast, negative change, and negative steadfast. You can get more complex and detailed from there, but any character arc should be able to fit into one of these categories.

The ghost and the abstract want typically speak to how the character starts out regarding the arc. For example, Harry wants love because he was left at his abusive aunt and uncle’s, but by the end of the book, he grows by learning he is already loved—his mother loved him so much, she sacrificed herself and gave him a special protective magic. Harry starts the story not knowing love is the most powerful force in the world, and he ends the story having learned that (his worldview changed).

In Cinderella, Ella’s ghost is when her mother dies. Her mother tells her to always be kind. Ella starts the story kind, and manages to remain kind despite her cruel stepmother and stepsisters—she remains steadfast, growing in resolve.

Both Harry and Ella are positive arcing characters.

The character arc will often represent a worldview or belief system, such as “Love is the most powerful force in the world” or “Kindness helps us weather trials.”

The 4 Elements

While technically a protagonist doesn’t need all four of these elements on page, it’s usually very beneficial for the writer to know what they are. When a protagonist doesn’t have these four things, she tends to feel a bit flatter (which is usually not what we are going for, but there are exceptions . . .). The two elements that should for sure show up on page are the goal and the arc.

4. Create an Antagonist to Create Conflict

Having a goal helps orient the audience toward a desired outcome, like having a destination at the end of a railroad. But if the protagonist can simply arrive at the goal immediately and smoothly, it’s not really a story. There needs to be resistance and opposition to the goal.

This is the antagonistic force.

What the antagonistic force is doing opposes or obstructs what the protagonist is trying to do.

If the antagonist doesn’t do that, it’s not a true antagonist.

The antagonist may be a “bad guy,” but it doesn’t have to be. It doesn’t have to be a villain or even a person. It could be a society, like the Capitol, or something natural, like a hurricane or pandemic. Or it could even be the protagonist’s self.

If the antagonist is something that can think for itself, it should want what it wants as badly as the protagonist wants what she wants—this will create the best conflict.

Because each entity is deeply driven to fulfill its wants and goals, when they meet, they clash fantastically.

Conflict doesn’t necessarily mean flying fists and shouting matches (though it can be that). Conflict simply means the struggle of opposition.

Even if your antagonist can’t think for itself, it has a path or a state of being that is messing with the protagonist’s plans.

While we think of most stories as having one main antagonistic force, realistically in a novel, there will be many. Figure out who or what is obstructing your protagonist.

Some say a story is only as good as its antagonist, because the antagonist is what’s challenging the protagonist (which also leads to his arc). Make the antagonist strong and formidable, a worthy opponent.

5. Figure out the Stakes

In order for conflict to be meaningful, it needs to carry consequences. Otherwise, it’s just conflict for the sake of conflict. If conflict happens, and nothing changes, so what? Who cares? Good conflicts have consequences.

There are two types of consequences:

- Stakes

- Ramifications

Stakes are potential consequences, and ramifications are the consequences that actually happen. Sometimes these things align, and what we thought would happen, does in fact happen, but sometimes they don’t align, and then we have a surprise or a twist.

Stakes are often defined as what the character has to lose, what is at risk in the story.

But when you communicate the potential consequences, you communicate the risk.

“If Harry doesn’t stop Voldemort, then the Wizarding World will be lost.”—the Wizarding World is at risk.

“If Katniss wins the Hunger Games, then she’ll live and be able to take care of Prim.”—Katniss’s life and the wellbeing of Prim are at risk.

Because you haven’t yet ironed out the story, you may not know for certain what the ramifications are, but it’s never too early to figure out the stakes. The best way to do this, for now, is to ask, what will happen if the character doesn’t get the goal? And/or what will happen if the character does get the goal?

As you answer these questions, don’t be afraid to stack on multiple potential consequences—usually the more at risk, the better. The risks can be big and broad (involving the whole city, the whole world), or personal and deep (one’s identity, wellbeing, or heart’s desire).

6. Write a Premise or Logline

At this point, you should be able to write a decent premise or a logline. A premise is the main idea of a story. It’s 1 – 3 sentences that say what the story is about, typically the setup. A logline is similar. It’s one sentence and is used to pitch or promote your story. While many people write their loglines after the story is completed, writing a logline or premise now will help 1) make sure you have the proper pieces for a story and 2) help you focus on the most important parts of the story.

A good premise will communicate who the protagonist is, what he desires (want or goal), what the antagonist is (which implies conflict), and what the stakes are. These may be stated directly or indirectly.

You may also add a sense of setting or worldbuilding, if the story calls for it.

Here is a logline for Mulan:

When Fa Mulan learns her weakened father must go to war to fight the invading Huns, she secretly disguises herself as a man to take his place.

Character: Fa Mulan

Desire: To take her father’s place

Antagonist: the Huns

Conflict: War (with the Huns)

Stakes: She could be discovered as a woman (which would bring dishonor to her family)

Write out a simple premise or logline. If you desire, you can play with the wording to make it sound more interesting (imagine you are trying to hook a reader). At the same time, you don’t need to stress much about the word choice yet, because you still need to write the story, and some of your ideas may evolve or change during the creative process.

If all your story pieces are there and you want to write this story, head to the next step.

7. Shape with Structure

Basic Structure

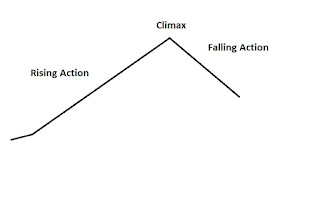

At the minimum, a story should follow basic plot structure:

The rising action is where the protagonist pursues the goal, runs into antagonists, and has to take bigger risks to get what she wants. This escalates the plot.

The climax is where the protagonist and antagonist go head-to-head, and one definitively wins the conflict.

The falling action is where we tie up any remaining loose ends and revalidate who won.

This is the basic shape to start with.

But many writers feel like this doesn’t give them enough direction.

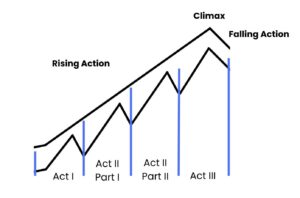

In reality, this shape is a fractal, and it should repeat itself (give or take) within smaller pieces, called acts, in a story.

Basic Act Structure

Most commonly, a story is viewed as having three acts (beginning, middle, end). Act I takes up the first quarter, Act II the second and third quarters, and Act III the fourth quarter.

Because the middle takes up half the story, many writers prefer to split it in two.

This means each quarter of the story should have a “peak” moment. As the story progresses, each peak gets bigger and more dire, until we reach the actual climax of the story. This will help ensure your story doesn’t have a boring beginning or saggy middle.

There are also other approaches you can use to add more detail to your structure. Three of the most popular are 7 Point Story Structure, The Hero’s Journey, and Save the Cat.

At this point, you may want to do some more brainstorming (or discovery writing) to figure out more of your story, or, if you have already done enough, order the scenes or chapters you have in mind in a way that will satisfy structure.

The “Peak” of Each Act

Whichever approach you use, often Act I’s “peak” will be the moment the character chooses definitively to go on the journey.

Act II, Part I’s “peak” will usually be either a significant event (conflict) or a significant reveal, that leads to the protagonist becoming more proactive.

Act II, Part II’s “peak” will usually be a big conflict that ends in a seeming failure. This is sometimes called the “All is Lost” moment, because that’s usually how it feels.

Act III’s “peak” will be the actual climax of the story.

If you have come up with major, pivotal scenes or chapters that affect the story in a big way, you’ll probably want to place them at these peaks.

The falling action of an act functions a little differently than the falling action of the whole story. In the falling action of an act, the character will be reacting to whatever big “peak” just happened, before going on to make the next climb. (Learn more about act structure here.)

Even if you don’t have the details worked out or if the story changes, considering structure early will give you a map on your writing journey.

8. Consider a Theme

Many writers don’t like to think about theme until after a draft of the story is written, and some never like to think about it. But like writing a logline beforehand, having at least some idea of your story’s theme, can help you write a more focused (and resonating) story.

A theme is an argument a story is making about life. This will actually often somehow tie back to the protagonist’s abstract want, ghost, and character arc.

For example, the theme of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone is “Love is the most powerful force in the world.” And the theme of Cinderella is “Kindness helps us weather trials.”

You don’t have to have the argument entirely figured out yet. But it’s probably a good idea to have the topic of a theme in mind. For example, the topic of Harry Potter’s theme is “love,” and the topic of Cinderella’s theme is “kindness.”

Is there a topic you want your story to explore? Is there a topic that you see emerging from your protagonist’s want, ghost, or arc?

Often that topic will have an opposite. For example, the opposite of love is hate. And the opposite of kindness is cruelty. This opposite will also usually show up in the story. The Dursleys, supposedly Snape, and Voldemort, all relate to hate, while Ella’s stepmother and stepsisters show cruelty.

Write down a topic and its opposite, and keep them nearby. Good ideas relate to the protagonist and the plot. Great ideas relate to the protagonist, the plot, and the theme.

Don’t stress too much about the argument if you are unfamiliar with how theme works, but keep the topics in mind as you write. Consider how those topics can be expressed in the story.

9. Expand Your Character Cast

Most stories will have more than a protagonist and antagonist. Most stories will have supporting characters.

It’s important to remember, though, that these are supporting characters. This means they are meant to support and facilitate the protagonist’s journey, not take away from it.

For this reason, rather than create them all uniquely from scratch, it’s often more effective to create them with the protagonist and her journey in mind. What allies and enemies will the protagonist need to grow? Who will challenge or test the protagonist’s resolve? Who will help her toward her goals? Consider the roles and types of people your protagonist and plot need.

Watch out for making allies too similar—this may lead to bland scenes and interactions. Instead, it’s more effective to emphasize differences between allies. And likewise, it’s often more interesting to find similarities between enemies.

Also, think about what characteristics you need to emphasize in your protagonist, then consider what kind of people will help you do that. Usually the best way to emphasize something, is to find a way to contrast it. So if you want to illustrate how your protagonist is kind, then you may want one or more supporting characters to behave cruelly.

Most stories will highlight one key relationship, such as a mentor and a student, the protagonist and a love interest, two best friends, a set of rivals, or co-workers. You may want to think about who the protagonist is in a key relationship with. This person will often have significant influence on the protagonist and the journey. This person often helps (or hinders) the protagonist’s arc.

10. Pick a Point of View

Most Common POVs

At the basic level, you have two options to write in: first person and third person. In first person, you write the story as if the character is telling it, frequently using the pronoun “I.” Third person is slightly more removed, and you write the story as if following the character, frequently using the pronouns “he” or “she” (or maybe even “they”). The Hunger Games is written in first person, and Harry Potter is written in third person.

Uncommon POVs

There are technically two other options, but they are unusual and unpopular. In omniscient point of view, the narrator can follow whomever, whenever, and however. The Book Thief is written from an omniscient point of view. New writers are discouraged from writing in this point of view because it’s very difficult to do well, and most (frankly) abuse it or use it out of laziness or ignorance.

There is also second person. With this point of view, the story is written by referring to the character as “you.” This is sometimes seen in “choose your own adventure” stories, but it’s almost never used in stories outside of that.

More on Third Person

Third person also breaks down into more types. Most commonly, third person limited is used. In third person limited, the narrator follows one viewpoint character at a time. If the story has multiple viewpoint characters, the narrator will usually only switch to a new character at a scene or chapter break.

A rule of thumb for writing in third person limited is that you should still write the story from that character’s mind and body. This means you can’t write what the character doesn’t know or doesn’t experience, while in that character’s viewpoint. Anything that shows up on the page must be what that character knows, thinks, feels, or experiences. Anything else is considered a viewpoint error by professionals.

Third person is a little more flexible than first person, but it’s also less intimate.

It might be a good idea to look at other books in your genre to see what point of view is commonly used.

11. Understand Scenes (and Summary)

For most stories, what happens is dramatized in scenes, not told in summaries.

Many writers have an idea of their story overall and rush into writing it, clueless about how scenes work. This can lead to poor or lackluster scenes, which is a problem because the audience will first be introduced to your story via scenes. The audience doesn’t know the brilliance of the full story, because they only read it one scene (or chapter) at a time.

A scene is one of the smallest structural units of a story. It happens in real time and shows characters acting in a specific location. The cornucopia blood bath is a scene in The Hunger Games. Luke delivering Leia’s message to Obi-Wan is a scene in Star Wars.

Just as the overall story has a goal, antagonist, conflict, and consequences, so should most scenes (though there are exceptions). And just as the overall story follows basic story structure, so should most scenes.

The difference is simply that scenes happen on a smaller scale.

At the cornucopia, Katniss’s goal is to get the bow and arrows, but the area is riddled with antagonistic forces—other fighting tributes. When she runs into them, it creates conflict. There are stakes: if she gets the bow, she’ll be able to have more food and better protection. If she doesn’t, she won’t. This peaks after she’s grabbed the bag instead and has her final dangerous encounter with a tribute. The falling action is her getting away.

In scenes, you should show, not tell.

Summaries are helpful in linking scenes and when it’s important for the audience to know, but not experience something. You can learn more about each here.

12. Write Your First Scene

If you haven’t already (I see you, discovery writers), it’s time to write your first scene. This could be the opening scene of your novel, but it doesn’t have to be. You technically don’t have to write in chronological order, but most writers do.

Check that Your Scene has . . .

Do yourself a favor and make sure the scene has what we just discussed: a scene-level goal, scene-level antagonists, scene-level conflict, scene-level stakes, and a scene-level “peak” (or mini-climax). Again, not all scenes have to have all those. But most scenes, for most stories, do most of the time. Maybe you decide your first scene doesn’t need all that; okay, but your second, third, or fourth scene probably does.

This scene does not need to be as dramatic as Katniss’s cornucopia scene. Consider Luke’s first scene. His goal is to purchase droids before picking up power converters, but he runs into resistance—the droids are the wrong kind, and his uncle wants him to clean up the droids right away (instead of getting the power converters), then one of the droids breaks. The “peak” is when Luke has successfully gotten two droids, and the falling action is him taking them home.

Not everything you write in here has to be perfect—this is only a rough draft. But the more you can follow these guidelines, the less trouble you will run into (and the less writer’s block you’ll have).

If this is your opening scene, make sure it hooks the audience. If you communicate the scene-level goal and stakes early on, it should help do that.

Keep Writing

After you’ve written your first scene, write the next and the next. If you have the proper plot elements in place, it should be easier to see what needs to happen next (because what happens now should have consequences that influence what happens next).

13. Write the Beginning

Assuming you are writing in chronological order, you’ll first write the scenes of the beginning (also known as Act I).

After hooking the audience, there are usually a few more things you’ll need to do.

a. Establish What’s Normal

Convey to the audience what life is currently like for the protagonist. This is often what’s “normal” to the character; it is at least “normal” compared to what happens later. So, in Barbie, time is spent establishing what Barbie likes to do every day. Even if it’s not normal to us, it’s normal to the Barbies.

Make sure to convey when and where the story takes place, and introduce any other key characters. Depending on the genre, you may need to also introduce worldbuilding elements, magic systems, or technology.

Continue to show who the protagonist is; convey her defining characteristics and skills and what she believes and values, especially those things that relate to her want, goal, and character arc.

Speaking of goals, don’t completely neglect scene-level plot elements. Even Harry and Luke have to deal with the antagonistic forces of their relatives in here.

b. Inciting Incident

The inciting incident is something that disrupts the established normal, essentially kicking off the main conflict. Luke hearing Leia’s message, Prim’s name being called out at the Reaping, the arrival of a Hogwarts letter, and Gandalf inviting Bilbo on an adventure are all examples of inciting incidents.

Usually this disruption will appear (now or eventually) as a problem or an opportunity for the protagonist.

c. The Protagonist Choosing to Move Forward

The peak of Act I usually shows up as the protagonist choosing to embark on the main journey. This is what Act I has been building up to. So after the death of his aunt and uncle, Luke goes with Obi-Wan. Once Harry learns what these letters are about (“Yer a wizard, Harry”), he goes with Hagrid to Diagon Alley. And in The Hobbit, this is Bilbo running to catch up with the dwarves.

Often the character will literally travel to a new location, but he doesn’t have to. He at least finds himself in a new state of being, a new situation.

Sometimes this moment is marked with an encounter with a big antagonistic force, but it doesn’t have to be.

14. Write the Middle

The middle is usually the biggest portion of the story. This is one reason many writers actually like to split it in half.

The First Half

Usually the character is pursuing a plan by this point and encountering new situations. Often in the first half of the middle, there is a sense of exploration. Any skills the character will need to defeat the antagonist will usually be learned here. This is also typically when new relationships are formed, or old ones are deepened.

Make sure the protagonist is still pursuing an overarching goal and running into antagonists and conflicts that carry consequences. The story should be escalating. The problems should get bigger and so should the stakes. It’s okay if the goal or plan changes or gets added to, but make sure there is at least a big goal almost always in play.

Near the exact middle of the story, there is usually another peak, a key plot turn called the midpoint. This may be a big conflict between the protagonist and an antagonist or it may show up as the protagonist learning new information, which alters his goal or at least his plan for getting the goal. Or it could be both.

For example, in Star Wars, this is when the Millennium Falcon gets pulled in by the tractor beam and Luke learns Princess Leia is on the Death Star. This shifts his big goal to that of rescuing Leia.

The Second Half

The second half of the middle usually feels more aggressive. Both the protagonist and antagonist are trying harder to get their goals. Each entity is trying to gain (or keep) the upper hand. The conflicts get bigger and so do the consequences. The rising action escalates until it hits another peak, where the protagonist and antagonist usually have a big clash.

Most frequently, this results in a defeat (or seeming defeat) for the protagonist known as the “All is Lost” moment. But even if the protagonist seems to win here, soon enough that victory will typically feel hollow or at least incomplete, like something is missing.

In any case, the middle usually ends with a lull—however brief or long that lull is.

15. Write the End

At the beginning of Act III, usually the protagonist gains something that propels him out of that lull. It may be new key information, a sudden insight, a new weapon, a mode of transportation—it can be almost anything, but whatever it is, it’s what gets the protagonist back on track to hit the climax of the story. She sees a way to achieve her big goal.

But it won’t be easy.

Because the antagonist is more powerful than ever.

The rising action hits the climax; the protagonist and antagonist go head to head in a clash where everything that matters seems to be on the line. All the major stakes seem to hinge on the outcome of this encounter. Whoever wins this battle will be the definitive victor of the story. Make this moment dangerous and dramatic.

While the protagonist doesn’t have to win, in most stories, he does. Whatever the case, the story then hits the falling action.

Use the falling action to tie up loose ends, validate what has changed or remained the same because of this journey, and convey what the near future looks like for these characters or this world. Like the beginning, you may want to establish the sense of a new normal.

16. Revise and Edit

Every story needs some revision and some editing. While you may need to take a break from the story for a bit (and maybe research more about story craft and structure), you’ll eventually need to come back to the project.

Just like the writing process can be different for different people, so can the revising and editing process. Some like to read straight through the draft and make notes of everything that needs to change. Some like to jump straight into editing. (And in fact, some writers even revise and edit as they are writing the first draft.)

When editing, it’s usually best to focus on the big stuff first. Are all the elements we talked about in the opening of this guide, there? Are they strong enough? Was there a clear goal or goals throughout the story? Did the character arc? Did you find ways to incorporate your theme’s topic? Or did you discover the thematic statement? Do you need to shape the characters, plot, setting, or theme more to be satisfactory? Typically, writers will have at least some sense of what needs to change.

Revise and edit the story to the best of your abilities, or until you feel ready to hire an editor (which you should do regardless, if you plan on publishing professionally). You may also want to find other writers or readers to read your manuscript and give feedback. One great place to find writers is our Apex Writers Group.

You don’t have to agree with everything others say, but you should at least listen to and consider any feedback that you receive.

Trust the Process

As you write and then revise your story, it’s important to know that it’s normal to feel extreme emotions. One day you may feel like you’re writing the next New York Times bestseller, and the next day you may feel like your story belongs in the toilet. Nearly all writers go through this emotional rollercoaster. Trust the process. You write a book one word at a time, and you can’t fix a blank page. It’s okay to take breaks, but try not to let your emotions get the best of you. Completing a novel is a process. Follow the process until yours is complete. With enough patience, guidance, and effort, you’ll get there.

Love this guide? Explore these concepts in depth in The Triarchy Method online course taught by September C. Fawkes. Need help with your novel? Check out Apex Writers Group and learn from industry experts.

About September C. Fawkes:

Sometimes September C. Fawkes scares people with her enthusiasm for writing. She works as a freelance editor, writing instructor, and writing tip blogger. She has edited for both award-winning and best-selling authors as well as beginning writers. September is best known for her blog (SeptemberCFawkes.com) which won the Writer’s Digest 101 Best Websites for Writers Award and Query Letter’s Top Writing Blog Award. When not editing and instructing, she’s penning her own stories. Some may say she needs to get a social life. It’d be easier if her fictional one wasn’t so interesting.