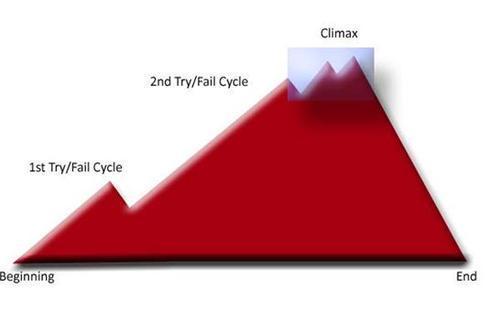

As your protagonist struggles to overcome a problem, in the past I’ve talked about how the protagonist goes through at least two try/fail cycles. Early in the story, in an inciting incident, the protagonist learns that he has a major problem on his hands. He then struggles to resolve the problem at least three times, and usually on at least two occasions, he must fail. The first attempt at resolving the problem is often an off-the-cuff attempt. On the second attempt the protagonist takes more decisive action, until at the climax of the story he or she faces the ultimate challenge. On a plot chart it might look like this:

Depending on the writing instructor that you have, those “try/fail” cycles may have different names. Some teachers will call them “obstacles,” others will call them “setbacks,” others “complications,” and so on. My mentor, Algis Budrys, used to call them try/fail cycles, and I do that out of habit, but it seems that no matter what you call them, they’re poorly-defined. Some complications seem like mere natural obstacles, while others deal with internal conflicts, and so on.

You see, as your protagonist tries to resolve a problem, there are a lot of things that can impede his or her progress. As a writer who often has to come up with these obstacles/setbacks/complications off the cuff, it might be helpful to think about the different types of problems your protagonist might face. So I’m going to pose a problem for an imaginary character, and then show you how you might brainstorm complications.

Let’s say I have a young woman. Her name is Kate, and she must get to Tabith. What kinds of obstacles might she face?

1) Intellectual obstacles. She might not know where Tabith is. Perhaps its location is secret, and one must first solve a mystery in order to get there. Finding the answer to this mystery might take half a novel to unravel. Or maybe she needs to find a guide. Or perhaps she is given the wrong directions and goes the wrong direction, or must solve a riddle as to the “best way to get there.”

2) Physical obstacles. Perhaps a swollen river blocks her road, or her sailing ship won’t sail due to lack of wind, or a trail can’t be found because no one has traveled there in ages. A physical obstacle could be a blown engine on a vehicle, a horse that takes sick, or a pack of wild dogs stalking the road. But a physical obstacle might also be some sort of injury that keeps her from moving forward.

3) Temporal obstacles. Very often, you can heighten the tension in a story by introducing a deadline. So perhaps Kate learns that she must reach Tabith in only three days. A wormhole between Earth and the planet will open in precisely four hours, and she has to reach the docks at Heaven’s Gate (at an L5 point in orbit) in 48 minutes, or she will never reach Tabith at all. Anything that happens—a lost bag, a shoe that comes off—becomes a time drag.

4) Social obstacles. Perhaps Kate is devoutly religious, and everyone knows that “Good girls don’t go to Tabith.” Her parents will disown her if she goes. Her friends shun her just for talking about it. For her own good, a friend tries to sabotage her trip.

5) Romantic conflicts. If Kate is going to Tabith, it might mean that she must leave behind someone she loves. Maybe the man that she loves first begs her not to go, and then demands to come with her, just to protect her. Or we could take it the other way. He’s already on Tabith, ready to be sold on the slave blocks, and she is going there in the hopes of buying his freedom.

6) Political obstacles. If you want to go to Tabith, your papers need to be in order. Getting a Visa is all but impossible. Or maybe the borders are blocked. Or “that planet is interdicted.”

7) Emotional obstacles. Kate might want to reach Tabith, but she might have a phobia about being whisked through a wormhole. Maybe she becomes homesick before she ever leaves. She’s in love with Bruce, and she knows that if she goes to Tabith, she’ll never see him again. Of course, there’s also fear: it’s that much harder to go to Tabith if you know that you’re going to die when you get there.

8) Monetary obstacles. Going to Tabith will cost everything that you have—and more.

9) Moral Dilemmas. Kate may really want to go to Tabith, but perhaps there is something of equal import that she must do. For example, she may want to go to Tabith to save her sister from slavers. But if she leaves, what will happen to her sister’s tiny daughter? She could be sacrificing one life to save another.

10) Self-inflicted Wounds. Very often, we’re our own worst enemies. Perhaps Kate is poor at planning, sleeps in late, or is forgetful. Maybe she’s greedy and is loath to pay the price of passage. In other words, she has some character flaw that she must overcome in order to succeed.

11) God as an Obstacle. This one isn’t used much in today’s world, but what if God tries to stop her? Like Joseph and Mary, perhaps she is warned in a prophetic dream. Or maybe she begins to have “hallucinations” that lead her on her quest. Or perhaps like Odysseus, the dead make their opinions heard.

12) The Antagonist as an Obstacle. I saved this one for last simply because it is often the most vibrant. Very often in life, we find ourselves pitted against someone who wants to impede our progress. The more powerful the antagonist, the greater the struggle. If you’ve got an angry neighbor making you miserable, the solution is easy. As my grandfather always said, “Always keep a shovel in the trunk of your car. You never know when you might need to bury someone.” But if like Frodo you have to go up against a wizard king with unassailable powers, terrifying minions, and unnumbered armies, things get a bit tougher.

The antagonist is interesting because, unlike the simple tree in the road that the protagonist can simply drive around, at any time the antagonist can take an active role to stop you, and they will go to any lengths. The next door neighbor might just slash Kate’s tires in an effort to make sure that she doesn’t make it to Tabith, while a mob boss might be more interested in slashing her throat.

A good antagonist surprises us by being clever. That means that he surprises the audience with his calculating ways. He always knows exactly when to show up.

The antagonist is also driven. If given an agonizing moral challenge, he’ll quickly sink to the occasion.

And a good antagonist is powerful. His minions rival Darth Vader in the use of the Force. They cast spells faster than the Wicked Witch of the West, and their armies are bigger than Hitler’s. Oh, and when all of that fails, he’ll kick the crud out of you with his bare hands—all while mixing a martini.

In short, developing a story is hard when you “Can’t come up with any ideas.” So keep this list handy, and next time you want to plot a story, take a look at it and give it some thought. A story will come to you pretty easily, I suspect.