In order to write a strong story, you almost always need complex characters. The three best ways to make any character complex are to create, consider, and explore their 1) seeming contradictions, 2) personal boundaries and value systems, and 3) layers of identity.

Admittedly, not every character in a story needs to be round and complex–it frankly wouldn’t be realistic. Flat and simple characters can be just as important. But for most stories, most of the key characters should have dichotomies, depth, and layers. This article can help you craft just that so you will have plenty of complexity to work with.

But first, let’s talk about what makes something simple versus what makes something complex.

What Makes Something Complex?

If we choose a subject and talk about it in “black and white” terms, the subject seems simple: Lying is dishonest, and telling the truth is honest.

Simple, right?

Complexity happens in the gray area—in other words, when we push “black and white” together.

Is lying always dishonest? What about sarcasm? Sarcasm often uses a form of lying, while conveying the lie isn’t true. If an audience knows it isn’t true, is it still dishonest? Or is it even considered lying? From there we can start dissecting dictionary definitions and debating more.

On the flip side, you can tell the truth in such a way, that it makes it sound like a lie. If you tell the truth with the intent to make people believe it is a lie, is it really a lie? Can it really be considered honest?

Now a subject that seemed simple has become complex.

Similarly, when we create, consider, and explore the gray areas of our characters, they will become more complex for the audience.

Through Contradictions

A character can become more complex when we smash together opposites, creating what seems to be a contradiction.

- Harry Potter: the most famous and (rumored to be) most powerful wizard in the world, and he lives in the cupboard under the stairs at his abusive aunt and uncle’s.

- Blu from Rio: a bird who doesn’t know how to fly.

- Frodo from The Lord of the Rings: the most unskilled, unqualified, and harmless person is the only one capable of taking the evilest magical object, the Ring, through the darkest lands to be destroyed.

- Judy from Zootopia: A rabbit who wants to be a cop (a contradiction within her society).

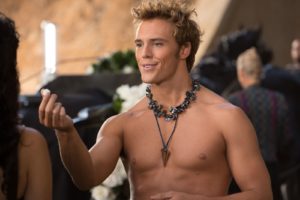

- Finnick Odair from The Hunger Games: long pampered and adored as society’s playboy and sex symbol, Finnick yearns for monogamy and shares a pure love for Annie that is unrivaled. Though he could have any woman in the country, he falls for a mentally disabled girl that he’s forbidden from marrying so the antagonist can continue to use him as a high society prostitute.

Made-up examples:

- An outlaw who is law-abiding

- A soldier who refuses to hurt anyone

- A vampire who doesn’t like drinking blood

- A princess who hates being royal

The contradiction need not be as obvious as some of these examples. Nonetheless, once you’ve smashed together contrasting features within the character, the gray area can be explored to find complexity. Why wouldn’t a vampire want to drink blood? How could a bird not know how to fly? Why might an outlaw be law-abiding?

If you are working with a side character, you may not need to go that deep (but as we see with Finnick Odair, you can). Some people in the writing world imply that simply giving a character a contradiction is enough to make them complex. But if a protagonist has a contradiction that is never explored or explained in the story, it is at best a lost opportunity and at worst, a method that distances the audience. Often the audience will be caught wondering about the contradiction and waiting for an explanation … that doesn’t come.

That’s assuming the contradiction isn’t just background information.

In many stories (perhaps arguably most), the contradiction will relate directly to the character arc. For example, in Rio, Blu must learn to fly by the end. And this may be true even of side characters, as Finnick Odair eventually becomes a symbol of pure love.

Sometimes the contradiction will be at the root of the protagonist’s personal journey. The very fact that Frodo is the least qualified is exactly what makes him the most qualified—anyone more worldly would be corrupted by the Ring long before reaching Mount Doom. At the same time, the external journey costs him his childlike innocence.

Similarly, Judy makes a big deal of proving that a bunny can be a cop, but the events of the story (plot), push her to face the fact that she herself is biased.

When working with contradictions, it’s usually worth keeping in mind that the more outlandish and center-stage the contradiction, the more likely it needs to be explored and explained in depth. The goal is to create complex characters, not caricatures. (Unless, of course, creating caricatures is the point of your story.)

With Stakes and Boundaries

Stakes are what are at risk in the story. As I shared in my article last month, they are potential consequences that can fit into an “If … then” statement (even if they aren’t written as one directly on the page).

For example:

“If Jeffery knows I ratted him out, then he’ll never forgive me!”

“If we don’t fight back, then Mack will take all our land, our homes, our lives we built.”

“If we don’t keep moving, this place will be swarming with aliens in a matter of hours.”

Notice that each of these statements includes a potential consequence—the “then” part of the sentence.

Stakes are important in storytelling for several reasons:

- They get the audience to anticipate a future point in the story. (Translation: They help hook and reel in the audience, by making them curious to see the outcome. The audience might want to see if, in fact, Mack does take all their land.)

- They explain why the events matter by answering the “So what?” question. The events happening in the plot only matter insomuch as they affect an outcome. This in turn makes the audience care about what happens. (For example, we only care about Frodo destroying the Ring because we know doing so could rid Middle-earth of Sauron’s evil. If we didn’t know the result, then we’d be asking, “So what if he destroys a ring? Why does that matter?”)

- They reveal character.

To learn more about stakes specifically, see “How to Write and Raise the Stakes More Effectively.”

Otherwise, we’ll dig into that third reason.

Screenwriter and story expert, Robert McKee explains in his book Story that “true character is revealed in the choices a human being makes under pressure.” This is where stakes come in. Stakes equal pressure.

They are key in rounding out characters, because if there is nothing at risk, then what the characters do, doesn’t really matter. It doesn’t carry any significance, because it doesn’t change any outcomes.

In some sense, we are what we choose to do. As J. K. Rowling once penned, it’s our choices that make us who we are, and I would also add, why we make our choices is important too. But what we choose to do when we have nothing to lose, typically doesn’t reveal as much about us, as what we choose to do when we have everything to lose.

Maybe your protagonist tells the truth to her parents about putting a frog in her sister’s bed. Does that really matter if there are no potential consequences involved? Telling the truth when there are no dire consequences is easy. Telling the truth when there are important things at stake is hard. What if telling the truth meant she would be grounded and could not participate in a talent show she’s been practicing for, for months? There is prize money involved, and she was hoping to use that money to buy a chemistry set. Chemistry is her passion and she wants to be a world-renowned chemist someday. Which is more important to her? A potential chemistry set or telling the truth?

This becomes a crisis, and a question of values, and what she chooses will tell us loads about what she values most—which may be at odds with what she professes matters most. This creates complexity.

When it comes to values and standards, we often think in black and white (there’s that simplicity again). I’m not a liar. I’ll do my best to avoid even white lies. But if I was stuck between telling the truth or lying to save a loved one’s life, well, I’d pick the latter. But if I picked the former, that would say a lot about me as well—it would say I value being honest more than someone’s life.

As you look at your character, rather than thinking about what your character will or won’t do, think about where his or her boundaries lie. How big do the stakes need to get for the character to consider doing something unsavory or unusual? Or perhaps, how small do they need to be? One character may kill someone as part of “collateral damage.” Another would only kill if the fate of the world depended on it. And some, not even then.

On the flip side of this, you can ask how big or small the stakes need to be for a character to do something noble. One character may help anyone who needs it immediately. Another may only help when it is convenient for them. And a third may only help in a life-threatening situation. For example, in Star Wars: A New Hope, Han repeatedly expresses he doesn’t want to help the Rebel Alliance. He’s only concerned about himself. But when the stakes get high enough, Han returns to fight. Deep down, he’s not actually as self-centered as portrayed. This makes Han more complex.

In the end, we can’t see a protagonist’s true character if we don’t include significant stakes.

Via Identity

Identity can seem like a vague concept, but it gets down to how people are defined.

Here in the U.S., I think most of us would agree that the most important component of identity is how we define ourselves, on an individual basis. These days, we hear much about individuals asking society to properly identify them the same way they identify themselves. But in another culture, perhaps one that values the collective over the individual, how a society defines you, may be more important—and how a society defines you, might actually be how you define yourself.

Self and society may influence each other. Or, they may not. You may have a person who defines herself one way on a personal level, but it’s at odds with how her society defines her. In his online course, Writing Mastery 2, best-selling author David Farland discusses exploring your protagonist’s identity to strengthen a story, and it’s helpful in rounding out the character, too.

By considering the different layers of identity, you can create a character that is more complex. If all the components of their identity are cohesive, then they are simple. If the components deviate from one another or are even at odds with one another, they are complex.

But it’s better to break this down before we get ahead of ourselves.

On the most personal level, we have the self. How does your character view himself? Who does he think he is?

As you explore this, it might be helpful to come at it from two different directions—the omniscient point of view you have as the writer, and the first person point of view your protagonist has.

As the writer, you’ll likely know things about your character that even he doesn’t know—or at least you should (because that makes great subtext). But with the first person view, you might run into perspectives you hadn’t considered.

People may define themselves based on personality traits, ambitions, faults, fears, beliefs—almost anything. I’ve also met people who define themselves by comparing themselves to others, through social status and money, from their likes and dislikes, even by the brands they consume or follow. Today we hear much about race, gender, and sexual orientation, as components of identity.

While exploring how your character is defined on the “self” level, it may also be useful to consider how she doesn’t define herself. What won’t she put into her identity? I’ve met plenty of young people who seem to define themselves by what they are not, more so than what they are.

After the self, we can move out into other layers. How does his close circle of friends and family view him? How does the character view himself in relation to them? What relationships are most important? Perhaps who the character thinks he is, is different from who his best friend thinks he is.

Again, we can move further out, to the community or society. How does his school or workplace perceive and define him? Or a club, town, or county? Or the media? For some stories, it might be pertinent to go out further than other stories. For example, in a small-town romance, you may not go out further than the town itself. In an epic fantasy, you might be dealing with essentially the entire world defining the character.

Another perspective worth looking at, is how an enemy or antagonist may view the protagonist.

Now, if all these levels were to align, the character would essentially be “what you see is what you get” (rather flat). Realistically, it’s highly unlikely for them to align perfectly. Some entities are more accurate at defining the protagonist than others. And almost none of us are accurate in properly defining ourselves.

Consider the identity of Jean Valjean in Les Mis. How he is defined is completely different based on who is doing the defining. To the bishop, he’s someone in need. To Javert and much of society, he’s a criminal. To Cosette, he’s a mysterious but loving father. To Marius, he is a savior. As an audience, we see that who he is—someone whose suffering and mercy are worth an afterlife of paradise—is at odds with who he thinks he is—someone who is constantly coming up short.

When you deviate the different levels, the character becomes complex—especially if he is trying to reconcile the differences (as Jean Valjean often does). This is doubly true if his identity is changing through the story.

Often at some point (and usually at multiple points), the protagonist struggles with identifying himself. Some in the scriptwriting world say, there is only one plot, the one that answers, “Who am I?”

In any case, each of these approaches will help make any of your characters more complex, as you dig into their “gray” areas–whether those are found in seeming contradictions, pushing and testing their boundaries through stakes, or in their scrambled, shifting identities.

About September C. Fawkes:

Sometimes September C. Fawkes scares people with her enthusiasm for writing and storytelling. She has worked in the fiction-writing industry for over ten years, with nearly seven of those years under David Farland. She has edited for both award-winning and best-selling authors as well as beginning writers. She also runs an award-winning writing tip blog at SeptemberCFawkes.com (subscribe to get a free copy of her booklet Core Principles of Crafting Protagonists) and serves as a writing coach on Writers Helping Writers. When not editing and instructing, she’s penning her own stories. Some may say she needs to get a social life. It’d be easier if her fictional one wasn’t so interesting.

***

Happening Soon on Apex

Tonight at 7 pm Mountain Time

Every week, Forrest Wolverton holds the Apex Accelerator Program. This program is designed to help motivate writers and help them get past the obstacles in their life to become the best writer they can be. There aren’t very many writing groups out there that have motivational speakers!

Monday at 5:30 pm Mountain Time

Come join us for Monday evening strategy meetings. We will be working to give authors tools, knowledge, and motivation to create original, best-selling stories and the self-defined successful careers they want. Some weeks, we will focus on high level strategic areas writers need to consider and plan for, and other weeks, we will get down to the details of strategy implementation. Don’t miss out. We meet every week at 5:30 MT. Come strategize!